What challenges should designers face now, as found at the GOOD DESIGN AWARDs.

FOCUSED ISSUES is a GOOD DESIGN AWARD initiative that depicts the future of design in society through the screening process.

FOCUSED ISSUES of this article

Progress of General Learning

Four aspect of creativity apparent in good design

2017.12.31

Does current education in Japan nurture creativity? We find creativity in all the distinguished figures who appear in Apple's 1997 Think Different ad campaign: Pablo Picasso, Albert Einstein, John Lennon, Martin Luther King, Jr., Mahatma Gandhi, and others. They drew from a deep well of inspiration and expressed themselves with keen determination. Still, misunderstanding creativity as something only extraordinary people have threatens to put it out of reach of ordinary people.

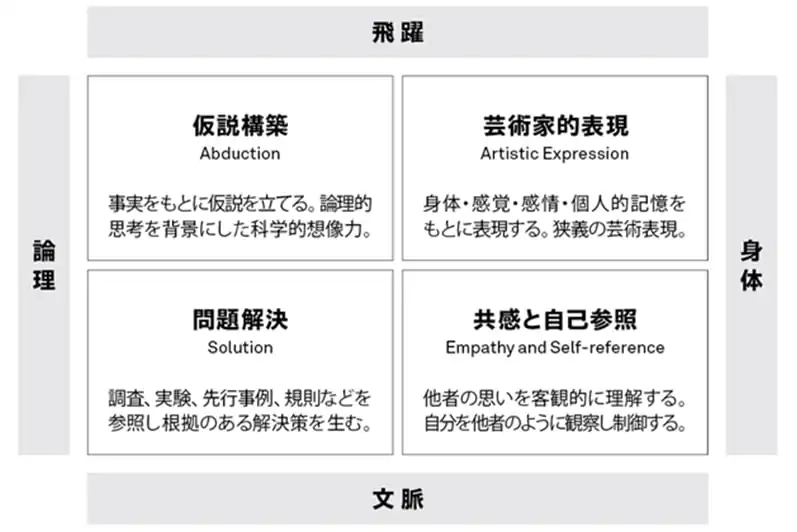

Before we can nurture the kind of creativity behind innovation and solutions to social issues, we should ask ourselves what creativity is all About. By no means is creativity limited to the ability to express ourselves well. We should not equate creativity with drawing or writing well, for example. Nor should we equate creativity with originality or eccentricity. Instead, I see four aspects of creativity: artistic expression, hypothesizing(abduction), problem-solving, and empathy/self-reference.

Four fields of creativity

Artistic expression is a physical kind of creativity. More specifically, it is a form of expression rooted in the body, senses, emotions, and personal memory. This is artistic creativity in the narrow sense, generally attributed to artists.

Hypothesizing involves establishing tentative theories by finding hidden relationships or unknown truth based on objective reality. It relates to what the American philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce called "abduction," different from deduction or induction. As a good example of this, imagine Newton hypothesizing About universal gravitation between objects after seeing an apple fall from a tree. Many outstanding scientists have applied this ability to pioneer scientific advances.

Problem-solving is creativity that yields sound solutions, based on an analysis of fieldwork or experiments and grounded in precedent, principles, and data. We might describe the ability to derive solutions by finding and tapping external resources as an ability to look beyond oneself. Unlike hypothesizing, which requires an abductive leap, problem-solving involves inductive reasoning. By collecting objective data and analyzing it according to established principles, anyone can arrive at similar answers. These answers vary, however, depending on what data you examine and how you examine it, so expert problem-solving depends on data-gathering skills, experience, refinement, and contributors' abilities.

Empathy and self-reference enable us to see ourselves in others, and vice versa. Through observation and objective analysis, both perspectives help us imagine what we or another person would think under the circumstances, which gives us some self-control and affects our behavior. As abilities not used solely for self-expression, they are essential to designers, who create tangible and intangible things used by others. They are also indispensable to actors, and to those who work in welfare or service industries. Normally, however, empathy and self-reference are not considered aspects of creativity. In the original sense, creation involves creating something from nothing. Although we could not describe settings such as cancer hospices as "creating" anything this way, few would deny that it takes creativity to work so closely with terminally ill patients, dealing with matters of life and death each day.

True creativity balances the four aspects of artistic expression, hypothesizing, problem-solving, and empathy/self-reference well. Accordingly, it can inspire design that transcends simple problem-solving. To distinguish design from art, people often insist that design solves problems, rather than being a form of artistic expression, but good design requires all four of these aspects of creativity. In particular, to me, the work of expert designers reflects their empathy, self-reference, and regard for physical sensations.

Products that nurture creativity

On the topic of creative learning, two Best 100 award winners this year were intriguing: Yamaha's Vocaloid for education and Primo Toys' Cubetto.

The first is Vocaloid-enhanced educational software that invites young students to make music and lyrics such as a class song together. Quite admirably, the product serves as a collaborative creative platform, drawing on shared emotions, rather than focusing on individual self-expression. Cubetto toys for younger children encourage cognitive development. By matching shapes—an early lesson in computer programming—children move a block-like wooden robot along a course. Here, a physical experience builds logical thinking, and playing with the toy also stimulates children's imagination through spatial recognition. Early gains in both kinesthetic awareness and logical thinking must be a first step toward nurturing true creativity. Toio from Sony also encourages cognitive development and teaches About programming. Future development of this DIY toy kit is interesting to imagine.

Children are not the only ones who need creativity, however. When we think of arrangements that also encourage adults to express their latent creativity, we realize that this area is still largely undeveloped. A few brilliant artists and scientists should not have a monopoly on creativity. Through good design, there must be unlimited possibilities to help cultivate creativity in everyone. Good design may depend on empathy and self-reference, but it also balances the other three aspects of creativity well, as a form of interdisciplinary knowledge that links many fields and shapes future lifestyles.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9de67050-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002 https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9de671a6-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002 https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9de6732e-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Keiichiro Fujisaki

Design Critique / Editor | Professor, Department of Design, Faculty of Fine Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts

Born in 1963. After working as the chief editor for the “Designers’ Workshop” magazine, Keiichiro Fujisaki got involved in writing articles, and editing magazines and books regarding design as a freelancer. Author of “Do Not Design,” covering the advertising firm Draft. Recently he edited a book called “T5: Front Line of Book Design in Taiwan.” Associate Professor since 2010 and Professor since 2016 at Tokyo University of the Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts, Department of Design. *Titles and profiles are those at the time of the director’s tenure