What challenges should designers face now, as found at the GOOD DESIGN AWARDs.

FOCUSED ISSUES is a GOOD DESIGN AWARD initiative that depicts the future of design in society through the screening process.

Focused Issues of this article

Design Created Together with the Next Generation

Looking at “cycles” of several 100 years: Taking time and effort in creating designs together with generations that will create the next era

2022.03.28

Thoughts behind the term “Future Generations”

We are in the middle of a generational shift. People belonging to Generation Y (Millennials) and Generation Z, also called “digital natives” and “SDG natives,” are becoming a majority of society inside and outside Japan. People of Gen Y and Z, who have a sense of value totally different from that of the current and past generations, will make up half of Japan’s working population by 2024. Half of the world’s population will be formed by people of Gen Z by 2030.

With such a fundamental change in sight, we are finding it more and more inevitable to consider younger generations in the context of corporate activities and in the world of design. It was against this background that I selected the theme “designs created together with the next generation.”

The term “Future Generations” was derived from the concept of sustainable development. The concept of sustainability, which was put forward at the meeting of the World Commission on Environment and Development (the so-called Brundtland Commission) held by the UN in 1987, defined as “meeting the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” The term “future generations” has since been a keyword in discussions About equality between generations.

The term “future generations” I use herein refers to two groups, one to which Gen Y and Gen Z belong, and the other to which generations of those who are not born yet belong. In other words, “design created together with future generations” is something that is worked on over a very long span of time.

Moreover, it needs to be kept in mind that products or services that target younger generations are not necessarily “designs created together with future generations”; such products may be made “for” future generations, but they are not made “together with” future generations. The same applies to designs that are mainly created by people of non-future generations, even if people of future generations have some part in the creation.

I was thinking, therefore, until I started the screening for the 2021 Good Design Awards, that there would be few “designs created together with future generations” in the strict sense, i.e., designs created jointly and impartially between people of non-future generations and those of future generations.

During the screening process, I must say that I found not so many entries that showed clear awareness of future generations, however, while I found certain projects quite interesting. A project that came to my attention is a book written for children, titled “Architecture for the First Time.” The book, filled with photographs and illustrations to show the fun of architecture, asks readers various questions About the art of architecture and encourages them to find their own answers. It also allows grown-ups and children to consider such questions, putting a spotlight on local architecture. This is a good example of people of non-future generations being in the same position as people future generations.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e604d10-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Designs created with a lot of time and effort do not break easily

Now, let met talk About the design process for “design created together with future generations.” The simplest approach is involving future generations in the making of the design. I therefore focused on the constitution of each team in the screening.

The screening process for the Good Design Awards has placed increasing importance on the process of each design, as it has become difficult to differentiate products based on price, function, or creativity; it is also no longer possible to judge projects based only on their deliverables. Instead, invisible factors, such as production process and team philosophy or stance, have become more important metrics for evaluation, and they will be more so in the future.

When it comes to “team-ness,” I think FUJIFILM, a regular recipient of the Good Design Award, has always been excellent. Generally, the quality of presentations at the screening panels varies considerably depending on the company and the presenter, but this is not the case with FUJIFILM; their quality is always very good, whether the presenters are salespeople, marketers, or designers.

I got curious and asked the company why and learned that it had something to do with abolition of the division of labor. According to FUJIFILM, in many of its projects, the company does not divide its business processes, i.e., R&D, product planning, marketing, etc., by job type; rather, researchers, designers, salespeople, etc. are involved in the entire process of a project as a team.

The scheme, says FUJIFILM, not only allows the company to develop products from multiple viewpoints, but also allows each project member to be more engaged. That is why, explains the company, its presenters invariably make such quality and realistic presentations.

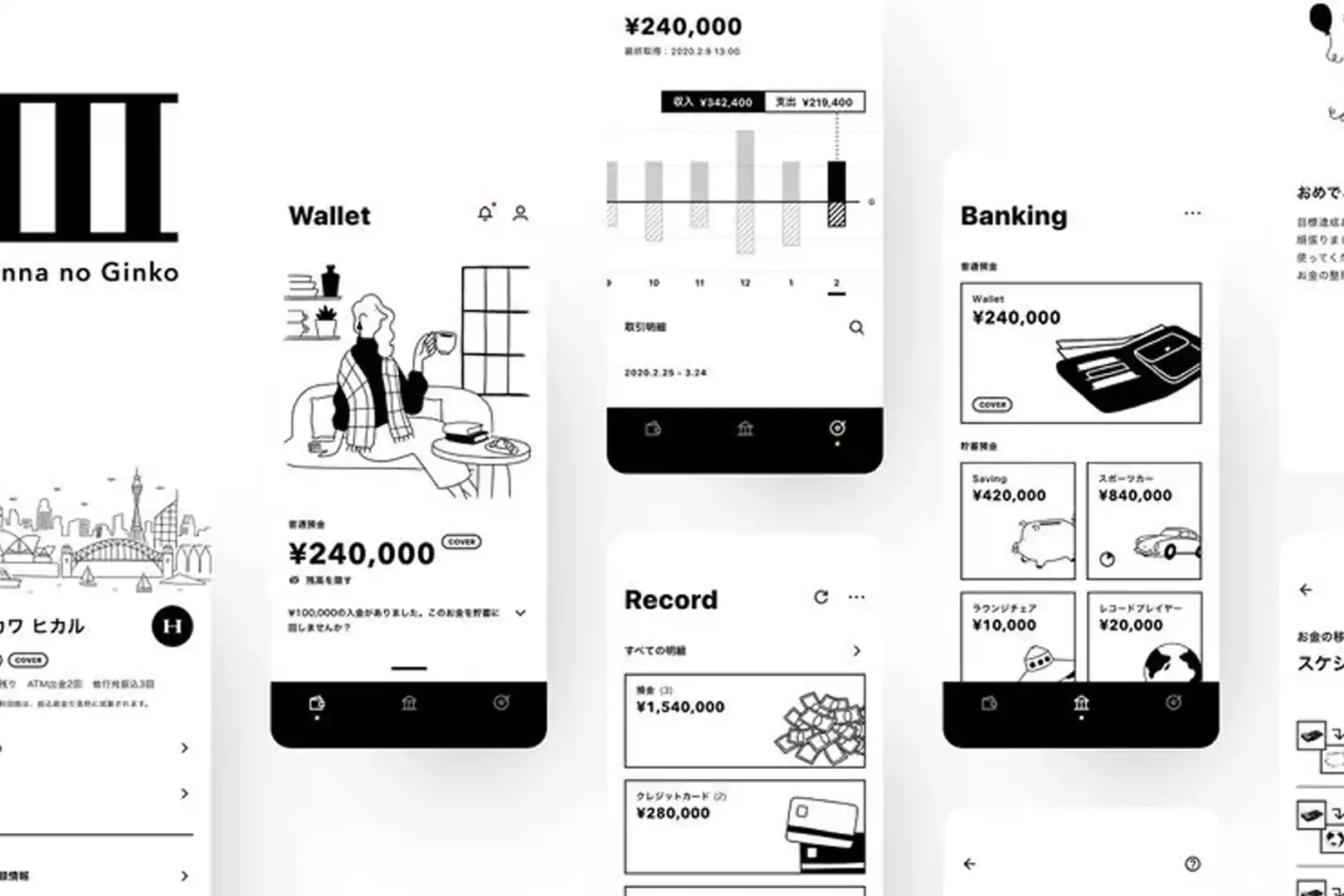

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e0d75cf-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Another project with exemplary team-ness is “Minna Bank,” Japan’s first digital bank targeting the generation of digital natives. According to Minna Bank, its banking app was developed through a painstaking process of repeated discussions and consensus forming, as the team comprised people from various backgrounds. Opinions often conflicted, says Minna Bank, between members from financial institutions and Millennial designers.

What these two examples share is the great deal of time and effort spent for the project. Given the nature of “designs created together with future generations,” I think it is inevitable that they require a lot of time and effort; it takes time to build a relationship between different generations or between people from different career backgrounds. Designs created with a lot of time and effort, meanwhile, do not break easily. Slow creation is essential to creation with future generations.

For reference: Kenichi Nagayoshi × Yoshiki Ishikawa | Design for everyone, which is achieved by “staying together”

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e5fd089-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Start by “being together,” continue by “staying together”

Another important keyword is “staying together.”

According to Minna Bank, the bank has an expert committee tasked with collecting feedback from users, and directors examine the collected comments at monthly board meetings. Through that process, all the members of the bank, including its executives, “stay together” with the target users, who belong to future generations.

The term “future generations” might blur the existence of actual people; however, the process of “creation” starts by taking an interest in individuals who comprise future generations and spending more time with them.

In fact, Minna Bank implements various initiatives such as social events for users and sharing information through various media platforms owned by it to create connections with its customers beyond its products and services. I realized this is a creative example to spent more time for staying together with users.

The Taitung Slow Food* Festival, a Slow Food event to expand slow food activities to communities, based on the traditional food of Taitung County, is also a project arising from “staying together.” (*Slow Food, a social movement aimed at promoting food culture that places increased value on healthy and eco-friendly food and on its producers, started as a call for rediscovering regional agriculture and food culture and a protest against fast living and fast food.)

The Taitung Slow Food Festival was initially launched for the purpose of developing the local tourism industry. With little to do in the county, which has few tourist spots other than the sea and mountains, the members started by spending time together in the earliest stage, and as a result, the community gradually expanded, leading to the creation of the festival.

Since the festival was activated by the “staying together” of its members, I would guess that they spend time together even when there are no festival-related tasks. A conventional design process starts from forming a team for the project and allocating tasks to each team member. It is safe to say that the process does not apply to “designs created together with future generations”; for the latter, one should start from spending time with people of future generations, exchanging thoughts and views.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e607e80-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Seek “cycles,” rather than durability or perpetuity

So far I have discussed “designs created together with future generations” from the viewpoint of creating them with young people in Gen Y and Z. I should also discuss design creation with the other component of future generations, that is, the generation of people who are not born yet.

An outstanding example of this perspective is “kitamoc,” a recycling-oriented business that was developed around the management of campgrounds.

Designs created together with the generation of people who are not born yet need to be worked on over a very long time span. Based on the concept of “the future will exist in nature,” kitamoc plans its businesses on a time span of 100 or 700 years. One hundred years is the cycle for growing and cutting down a planted tree, while 700 years is the cycle of eruptions of Mt. Asama, at the foot of which the company is located.

What surprised me even more than the long timeline is that it was the company’s employees who spoke About it in a matter-of-course manner, not only the representative who came to speak About it. I realized then that everybody working at kitamoc intuitively knows what it means to create a design together with a generation or generations of people who are not born yet.

Through this case study, I realized that “designs created together with future generations” are not simply accomplished by creating something durable and lasting. Rather, one should pursue “cycles,” so that future generations can decide what role a design will play when its initial one comes to an end. The concept of “designs created together with future generations” is akin to the “cradle to cradle” design concept, which seeks to reuse all waste materials by aligning manufacturing cycles by humans and natural cycles.

Indeed, not only humans but also nature is one of the stakeholders of “designs created together with future generations.” This was a big revelation to me when I was musing over this Focused Issue.

Whom is design is created for? Is it created for stakeholders other than current consumers, such as future generations, natural environments, and the Earth? These questions will be asked more and more often in the future.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e60777f-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002Now, let me propose three steps to increase the number of “designs created together with future generations.”

That is, “be” together, “be” sharing, and “be” creating.

We grown-ups tend to start from the step of creating, but we should start from “being together” with people of future generations, who have a sense of value completely different from ours. Through such efforts, it is possible to share thoughts and views with them, which will lead the creation of designs together. I believe that not skipping the first two steps is the key for outstanding “designs created together with future generations.”

Yoshiki Ishikawa

Public Health Researcher | Well-being for Planet Earth Foundation

Yoshiki earned a bachelor’s degree in Health Science from the University of Tokyo, a Master of Science in Health Policy and Management from Harvard School of Public Health, and a PhD in Medicine from Jichi Medical School. As a public health researcher, entrepreneur, and science journalist, Yoshiki is working at the intersection of science, business, and government as a catalyst with the aim of advancing the well-being of society. *Titles and profiles are those at the time of the director’s tenure