What challenges should designers face now, as found at the GOOD DESIGN AWARDs.

FOCUSED ISSUES is a GOOD DESIGN AWARD initiative that depicts the future of design in society through the screening process.

2024 FOCUSED ISSUES

Considering “A Small Step, Design Leaps”

Decolonization of Design in the Context of “Pluriverse” — Arturo Escobar × Yutaka Nakamura

2025.3.5

Yutaka Nakamura, a Focused Issues Researcher, presented “Decolonizing the nature-culture-economy ecosystem with inner creativity” as his recommendations for FY2024. To further deepen the recommendations, we approached Arturo Escobar, an anthropologist and professor emeritus at the University of North Carolina, for a dialogue.

Can’t we resist this powerful trend of global capitalism sweeping the world and the logic of capital defining society and culture?

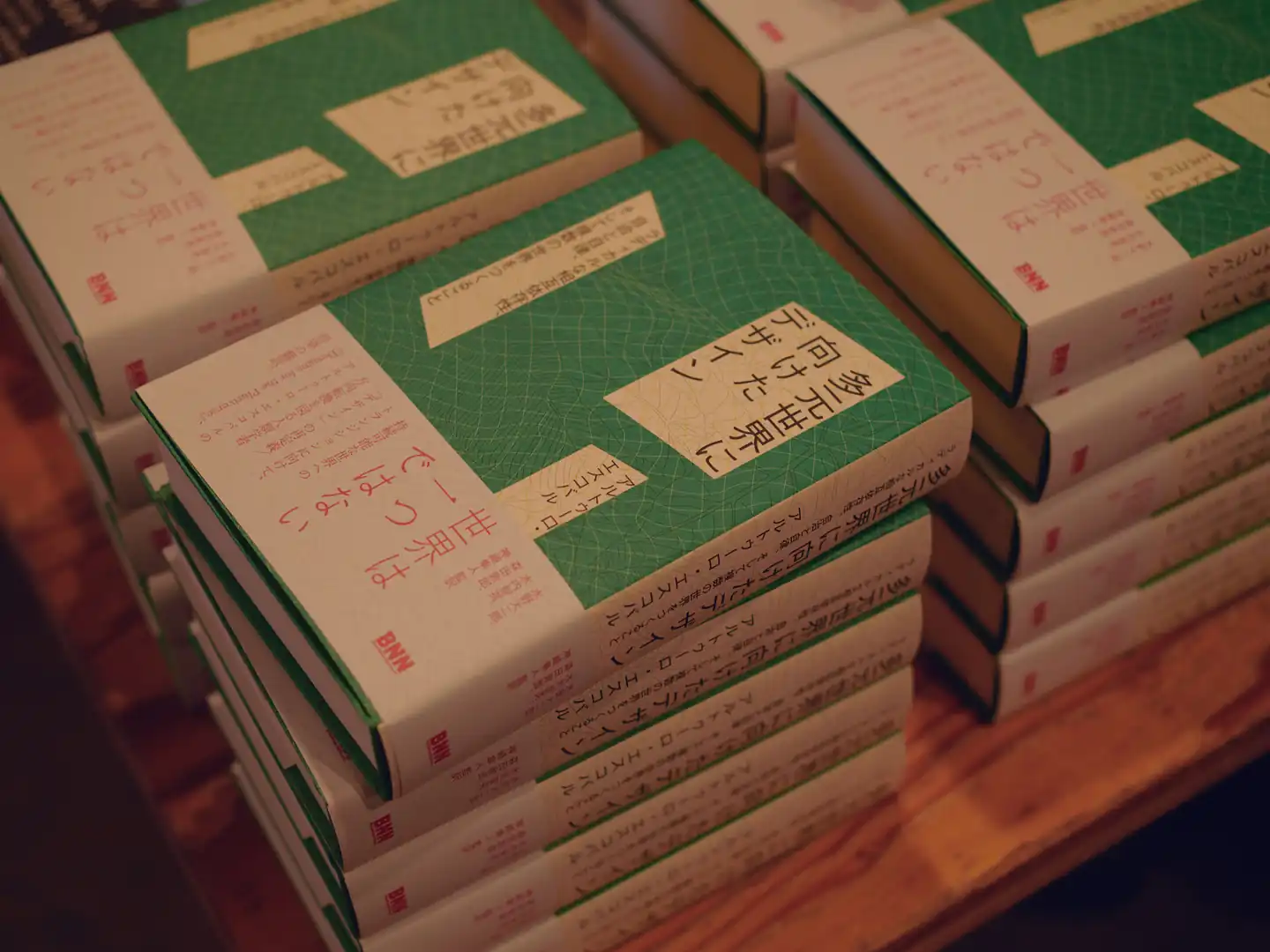

As a countermeasure, Escobar’s “Pluriverse” concept provides a perspective. His book, Designs for the Pluriverse, which was translated into Japanese in 2024 and drew wide public attention, explores ways to create multiple futures rooted in places rather than the single future of modern Western capitalism.

In this article, through the dialogue between Nakamura and Escobar, we explore the possibility of design for a pluriverse, or the fusion of design and anthropology.

Design to reduce isolation and promote collaboration

Nakamura: I put forward a proposal in the 2024 GOOD DESIGN AWARD Focused Issues, “Decolonizing the nature-culture-economy ecosystem with inner creativity.” Decolonizing design is a key issue in the proposal—how to move away from structures where design reflects and even reinforces power gaps between nations, races, ethnic groups, classes, and genders. Among this year’s GOOD DESIGN AWARD winners, there were several attempts to address and overcome this problem. The three works I will introduce this time all embody the principles of my recommendations.

The first is the RESILIENCE PLAYGROUND PROJECT, which was also selected for the top prize. It is a project that cut across the fields of medicine and playground equipment to develop play equipment on which anyone can play regardless of disability. What they found was children, who were thought to be in difficult conditions with severe disabilities or serious health conditions, playing in their own unique ways. Through design to support children’s inner creative activities, they created a playground where anyone can play.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/22683The second topic I would like to talk about is baachan business (grandma business). As you know, Japan is an aging society. Recently, the words “elderly nuisance” have become widespread, creating a generational divide. In order to change society’s attitude toward an aging society and the elderly, the project has launched a new entity that allows people aged 75 and over to participate. For example, the baachanshinbun (granny newspaper) is a well-designed newspaper written and published by the grannies of the local town. It has a lot of news and information about the local town.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/27504And finally, I would like to introduce women farmers japan. It is not limited to rural areas, but in many cases Japanese society still has a strong male advantage. However, in this project, women farmers have created their own support communities and are taking on the challenge of supporting the independence of women in rural areas and solving the problems of farming in mountainous areas by “turning the wheels of community and business,” which has never been seen before in the agricultural world.

https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/24662What all three have in common is that they are trying to reconstruct and integrate in their own way the “culture” and “economy,” which are often divided in the business world. It’s not just about profit, it’s about cultural renewal and a business that inspires creativity within each of us.

Escobar: Thank you. I felt that these three approaches have in common the idea of reaffirming connection and community, thereby reducing isolation and encouraging collaboration. I think inner creativity is also linked to community creativity.

This makes more sense, especially in the United States, where I live, a country known for its radical individualism. The sense of community is mores alive in Japan and Latin America. But in the US, there’s basically no community. Globalization has rapidly led to the dissolution of communities; it has been a war on everything communal and collective. It increased the pressure towards individualization, driven by economy and technology.

The three examples you mentioned run counter to the trend of globalization, which is market driven, profit driven, and consumerist and individualistic. There are many creative experiments and opportunities at the communal and local — in fields such as communal living, manufacturing, small businesses, media, food and agricultural production, and more. These activities might create or strengthen local autonomy. That increased local autonomy prevents companies from monopolizing the value of their designs, their decisions, or the value of play in their communities, and preserves the value of creating something together.

Why has “Economy” become separated and viewed as special?

Nakamura: As you point out, the three examples I have presented are all against the forces of globalization and radical individualism.

On top of that, I would like to have a dialogue with you by linking it to the discussion you are developing in Designs for the Pluriverse. The “Pluriverse” described in this book is not limited to the traditional values of Western-centrism, colonialism, and capitalism, but represents an attitude of looking at other worlds that are also numerous and interconnected. What I want to ask you is, as an anthropologist/designer, how can we push Design for the Pluriverse? For example, what specific strategies can be used to overcome the challenges of bridging dominant design paradigms with localized and vernacular forms of knowledge?

Escobar: We should start with how modern behavior, knowledge, and ways of being and doing were defined. Since the invention of the capitalist system, the economy has been rapidly rationalized.

There are two important books to understand its history. One is From Mandeville to Marx: The Genesis and Triumph of Economic Ideology, in which French anthropologist Louis Dumont studied the origins of the economy as a cultural invention. The other is Karl Polanyi’s The Great Transformation: The Political and economic Origins of Our Time. What these books show us is that at some point in Western history, reality as a whole became fragmented. In other words, it fragmented what should actually be one continuous reality – economy, politics, religion, culture, society, and the individual – as if they were separate.

As Michel Foucault successfully analyzed in The Order of Things, the modern episteme (the overall framework of knowledge that underlies each age) crystallized at the end of the 18 century with the development of economics, biology, and linguistics. I mean, the very idea that we are economic beings above all else is something that has been gradually formed. And we still live by the classical economic blueprint since Adam Smith that the economy is dominated by so-called “free” or “self-regulating” markets. Originally, economics should be just one academic field such as political science, sociology, psychology, or humanities. Nevertheless, we see the economy as something special. That’s why economists are regarded as being so important in society. Because they are regarded as priests whose knowledge is essential to control markets, production, and manufacturing in the material world.

But not all societies were built on that basis of the division of reality into allegedly autonomous spheres (the economy, the social, the cultural, the political, and so forth). Rather, in many societies, it has been largely preserved as a continuum of existence, where what we call economy is connected to culture, society, religion, and spirit. I mean, a more holistic understanding. In East Asia, represented by Japan, there is a cultural understanding from Buddhism, Taoism, and other spiritual traditions that all living beings are deeply interconnected and interdependent.

But in modern times, in many ways, the culture was violently torn apart. The interdependencies between individuals and communities, between humans and non-humans, between nature and culture, and between humans and nature have also collapsed and been destroyed – what we call anthropocentrism in modern society. That’s why it’s difficult to establish a dialogue between the modern economy (such as the corporate economy) and the vernacular economy in order to transform the way we think about the economy.

Modern economists and business models operate on the assumption that the individual is the consumer and that the economy is one and driven by markets. The purpose of the economy is regarded to be to generate profits. But in a vernacular community, such purpose doesn’t make much sense. Of course, it’s also true that the Western economic view has assumed the hegemony and is slowly encroaching on every community around the world. But there are still ways to resist that trend, like these three examples introduced this time. There are many languages, concepts, and methodologies that allow us to think about the economy from a different perspective, such as ecological economics, the Circular Economy, the Regenerative Economy, Feminist Economics, and social and solidarity economies.

One of my favorite studies is by Australian geographer and feminist geographer Katherine Gibson and North American geographer Julie A. Graham. What they did was build a framework for what they call the diverse economy. It is a framework and methodology to understand the economy as made up of capitalist, alternative capitalist, and non-capitalist economic practices. They call it “Post-capitalist Framework” or “Post-capitalist Politics.”

But these studies are still far from mainstream. The mainstream is still a mechanistic individual-centered, profit-centered, economic mindset, which is basically seen as purely organized in and by markets. What I want to say here, however, is that unless we grasp the historical background of such economic thought, the discussion about alternative economies will end at the superficial level of business.

Can design lead to “Pluriversal De-economy”?

Nakamura: Modern corporate society is basically based on the economic view you described, and if you have a more alternative view of the market, like the vernacular economy or ecological economy, it is very difficult to have a dialogue with a corporate society that is framed in a modernist way. You also mentioned the work of Katherine Gibson and other new attempts to change and reframe modern economic views and thinking.

Escobar: That’s right. I call what Gibson-Graham were trying to do “Pluriversal De-economy.” I mean, I want to question the ontological naturalness of the modern economy as the only way to understand the economy. I would like to question the fact that Western modern economic understanding is taken for granted as the only possible one, or at least the best one. Included in the modern Western view of economics are the infrastructure and ideology of capitalism, the narrative of competition, and the individualistic and consumer-oriented view of humanity.

All the practices of living in a capitalist economy – is economic and human narrative, its specific infrastructures, capitalism, its concrete designs, and the practices that we do every day in a capitalist economy – are a complex, intertwined civilizational complex that took a long time to develop and become consolidated. This is why it is very difficult to understand and question the economy ontologically.

Nakamura: Nevertheless, I would like to think about the possibility. Even though the tide of globalization is interfering with local economies and forcing the whole planet under the umbrella of classical and modern economic views, I think that there is also a possibility, especially for vernacular knowledge, as a form of animism. Latin America, for example, embraces spiritualism with its own sense, and I think it’s rooted in their daily lives, their daily routines, their actions and their habits. There are similarities in Japan, which is why the concept of the “Pluriverse” that you propose is easily accepted by those who were born and raised in the country.

And I think design can be a gateway to rethinking alternative ways of the economy. However, if we look back on history, we have to be cautious. Because the GOOD DESIGN AWARD, which started in the 1950s, also started as an award for a kind of industrial design. However, in the past 20 years or so, social activities have come to be considered as “social design.” In that sense, I think design may be the beginning of rethinking economic models.

Escobar: Yes, that’s correct. You mentioned the fact that in Latin America many communities (particularly indigenous and Afrodescendant communities) maintain a unique kind of spiritualism, and we need to think about what these spiritual worldviews, cosmologies, and ontologies mean today. You can ask theoretical questions, or you can ask questions that lead to practical applications. What would happen to design, if we take as a starting point the premise and spiritual worldview that the whole world is alive?

Latin American indigenous peoples continue to defend vernacular views of the universe in which for instance mountains and rivers are sentient beings. People in vernacular communities understand that. Of course, fewer and fewer people may have that feeling, but many still do. They don’t think in terms of economic growth and development. They think in terms of what is called Buen Vivir (Good Living), a holistic understanding of life that celebrates life in itself.

So what is the Good Living for those communities? A good life should incorporate not only material and economic aspects, but also spiritual, cultural, ecological, mental, ancestral, and community perspectives. This is a cosmic or worldview different from the economic mindset that prevail today.

This kind of “Relational Ontology” is observed in various parts of the world. Take, for example, the African philosophy of Ubuntu. It means “I am because we are” in South African Zulu. In ubuntu thinking, human beings are not seen as independent beings, but as beings who live in interaction with others. It also includes the spirit of solidarity and care, and that they should live by helping each other, without assuming independence or individuality as supreme. I have also recently published a book on this subject called Relationality: An Emergent Politics of Life Beyond the Human, with two colleagues, Michal Osterweil and Kriti Sharma.

Nakamura: Environmental activist and thinker Satish Kumar recently visited Japan for the first time in a while because the Japanese translation of Radical Love (translated by Shinichi Tsuji and edited by Munenori Ueno, Yukkuri Shobunko) was published. He also wrote a book titled You Are, Therefore I Am (translated by Osamu Ozeki and Sawato Ozeki, Kodansha Academic Library). He was born in British India, and he also explores relational ontology. The title is the turnover of the famous thesis of Descartes. It’s also interesting to note that the subtitle of the book is “A Declaration of Dependence,” which is a flip of “The Declaration of Independence.”

It is not necessarily a declaration that we should live in complete dependence, but is supported by the recognition that our existence itself is already interdependent in a complex system. In this respect, it overlaps with Bruno Latour’s assertion in his Fictional ‘Modernity’: Scientific Anthropology Warns (translated by Kumiko Kawamura, Shinhyoron Publishing) that we have never been a modern man who divides nature and culture, subjectivity and objectivity, human and non-human, and treats them dualistically and purifies them individually.

Design anthropology paves the way to “decolonization”

Nakamura: How will relational ontology affect my research and applied field of design anthropology? Profitability and efficiency still come first in the business environment. But I think design can provide an alternative for transition. For example, a linguistic approach is only one way to persuade people to change their behavior. But I think that design itself can persuade modern thinkers nonverbally, not just through sight, but also through other senses, to help them actually shape economic alternatives. This is because design contains nonverbal characteristics that take us outside of a logocentric understanding. I suppose design could work directly on habitus, which Pierre Bourdieu once defined as the “unconscious.” How do you think relational thinking can be incorporated into the design process to promote economic alternatives?

Escobar: I think first and foremost that we should have the willingness to rethink the historical and ontological mandates of growth, profit, efficiency, and the individual. We all know that growth supremacism is very harmful to the planet. The pursuit of profit can be a motive, but it should not be the only consideration. We have to develop different value standards. Ecological economics has a set of methodologies for leveraging value beyond monetary value. There are many other ways to add value to what human beings do. Society is far richer and larger to measured everything in monetary terms.

There is a book that I really like. Its title is Designing Regenerative Cultures, written by Daniel Christian Wahl. What’s interesting is that this book is very similar to our book on Relationality in that it emphasizes the shift from a human-centered, dualistic mindset to one that emphasizes interdependence and connection. He develops his theory and explains the practical examples of regenerative economy and regenerative design in a very clear way for designers. This book is an example of a growing field of alternative economics from a design perspective. I also think that there is a growing movement to question the fundamental principles of economics. Because as modern mainstream economics, neoliberal economics is destroying the planet. I believe that it is important to think at the regional level and to investigate how by working together local economies can foster larger economies from the bottom up.

Nakamura: That’s interesting. I am particularly intrigued by the so-called Global South and Asian societies, the non-Western ways of living and thinking that lie at the heart of promoting the idea of “inversion.”

As a last question, can you talk about decolonization efforts? Colonialism has been a problem for many years, and I think that dynamics is probably still going on. I think the reason behind that is not just pure power imbalance, but strength imbalance in various aspects. That imbalance is not necessarily equitably juxtaposed or distributed. That’s the problem with the whole postcolonialism debate.

Given the criticism toward traditional development models, do you think that design anthropology can contribute to decolonization in the field of design itself? I ask this question because I think design also has the risk of re-colonizing people. Still, I think alternative models of design will create new fields. I believe that people can rethink the dynamics of colonization, rethink the divide between nature and culture, and rethink the modern economic framework, truly develop and create new ideas. How do you evaluate efforts and design for decolonization?

Escobar: I agree with you very much. But perhaps the uniqueness of design anthropology lies in its insistence on decolonizing both design and anthropology. Anthropology still needs to be decolonized. In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a real critique of the entanglement of anthropology and colonialism. There was an attempt to diversify anthropology beyond a single anthropology, as a counter to the dominance of Anglo-American anthropology. This attempt was called “world anthropologies”. Professor Shinji Yamashita was an active participant in these debates.

However, anthropology has not yet been completely decolonized as an academic discipline. Decolonization cannot be accomplished only theoretically, it has to be pursued through engagement in practice. In this sense, design also offers anthropology the possibility to engage in practices that transcend subject-object relationships. The power of design anthropology is not to objectify its subjects. In fact, for the past 20 years, anthropology has sought to merge with design.

But we’re only halfway there. I think a lot of the trends in design anthropology are about training anthropologists to work in conventional design practices or training designers to think more anthropologically about culture, to give them some background in anthropology. This might be important but insufficient. I certainly believe there is a lot of hope and potential for the convergence of design and anthropology, but the connection between the two needs to be deeper.

Nakamura: I strongly agree. Multimodal anthropology, anthropology of response, business anthropology, and multispecies anthropology in recent years seem to be attempts to explore alternative forms of knowledge beyond the Western forms of knowledge, particularly the production of representational knowledge. But as you point out, most of them are still in the academic world. It seems to me that new practices arise when a relationship is created between design and anthropology that goes beyond the superficial fusion of the two and shakes their respective unconscious assumptions and methods.

A report summarizing this year’s Focused Issues activities will be published in this journal soon. It highlights key discussions, including the recent expert roundtable, and brings together insights from six directors and researchers who examined a wide range of entries. The report also presents concrete actions as proposals. We hope you look forward to this deep dive into a year of exploration!

Arturo Escobar

Anthropologist born in Colombia in 1951. Professor Emeritus, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, USA. Adjunct Professor in the Ph.D. program in Environmental Sciences at Valle University in Cali, Colombia.

Yutaka Nakamura

Anthropologist|Tama Art University Professor / Atelier Anthropology LLC CEO / KESIKI Inc. Design Anthropologist

Nakamura is a cultural anthropologist and a design anthropologist. Professor at Center for Liberal Arts and Sciences, Tama Art University, CEO at Atelier Anthropology and in charge of Insight Design at KESIKI Inc. His research explores social design related to violence and de-violence in “peripheral” spaces, while actively engaging in social implementation with various companies, designers, and business leaders. At Tama Art University, he leads the Circular Office initiative and the Division of Design Anthropology at Tama Design University. Walking the Margins of America: Anthropology on Journey [Amerika no Shuen wo Aruku: Tabisuru Jinruigaku], Heibonsya, 2021 [in Japanese]; Harlem Reverberated: Voices of Muslims on the Street, Editorial Republica, 2015 [in Japanese], and others.

Ryo Hasegawa

Writer

Hasegawa assists with writing structure and articulation, supporting individuals, companies, and media in their communications, with a focus on technology, management, and business-related content. Notable editorial collaborations include The Future of Work in 10 Years (Takafumi Horie & Yoichi Ochiai), The Evolution of Japan (Yoichi Ochiai), THE TEAM (Koji Asano), and The Formula for Career Success (moto), among others. His background includes studying at the University of Tokyo (Interfaculty Initiative in Information Studies), working at Recruit Holdings, becoming independent, spending three years playing poker in Africa, and continuing his career today.

Shunsuke Imai

Photographer

He was born in Minamiuonuma City, Niigata in 1993. He became independent after working for amana Inc.

Masaki Koike

Editor

Editor. He does planning and editing in multiple media, mainly in collaboration with researchers and creators.