To the place where "good design" was created

Good design, excellent design, design that opens up the future, ideas that move people's hearts, and actions that lead society always have small beginnings.

Interviews with designers at the birthplaces of good design to find hints for the next design.

Destination

Isono Shokai Co., Ltd. / Osamu Watanabe Architects

A utopia can be created (Part 1)

2024.06.13

In recent years, a construction method called bricolage has been attracting attention. It is a method to collect what already exists and anything immediately at hand, and change them into something new. Johnson Town, which is a revitalized housing area for the U.S. forces in Japan in the Showa era, is a good example. It is a broad-minded ‘town’ that is open to anyone, which could not be achieved by deliberate design. It is a town with a community where various generations live, work, and interact. However, it used to be a run-down place. How was it capable of changing into an ideal environment? We heard from Mr. Tatsuo Isono and Mr. Akio Isono of Isono Shokai, the owner and manager of the town, and Mr. Osamu Watanabe, the planner and designer of the architecture firm.

Asset called “Beigun (U.S. military) houses”

— This is my first time to visit Johnson Town. I was surprised that the sky feels so open. On the spacious site reaching 2.5 ha, housing and shops are built in harmony with green, and people in the square can be seen enjoying conversation. There is no litter, and the traffic is regulated. This is a “town” where children, elderly people, and people with disabilities can live peacefully.

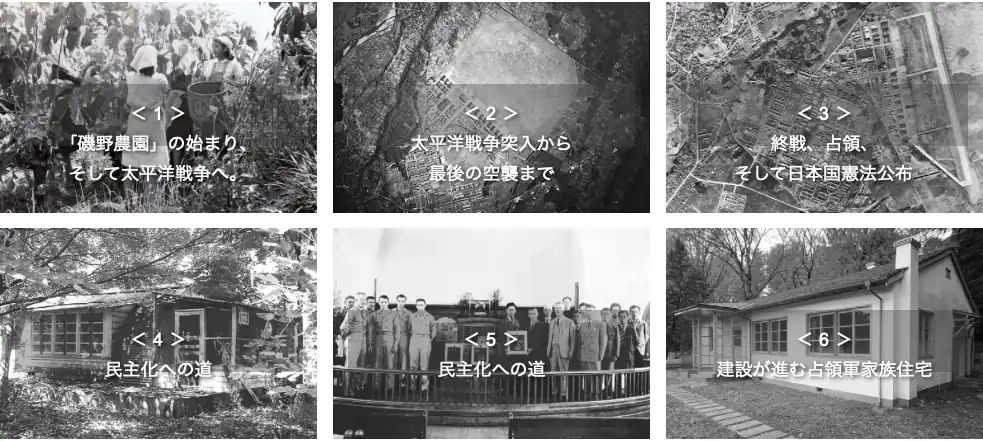

Tatsuo Isono (President, Isono Shokai): Originally, this used to be farmland that my father acquired before the war when it was cheap.

— Currently there are 80 housing units including 24 one-story houses called “Beigun houses” and 40 buildings called “Heisei houses,” “Nihon kaoku (Japanese house),” and “Sekisui M1.”

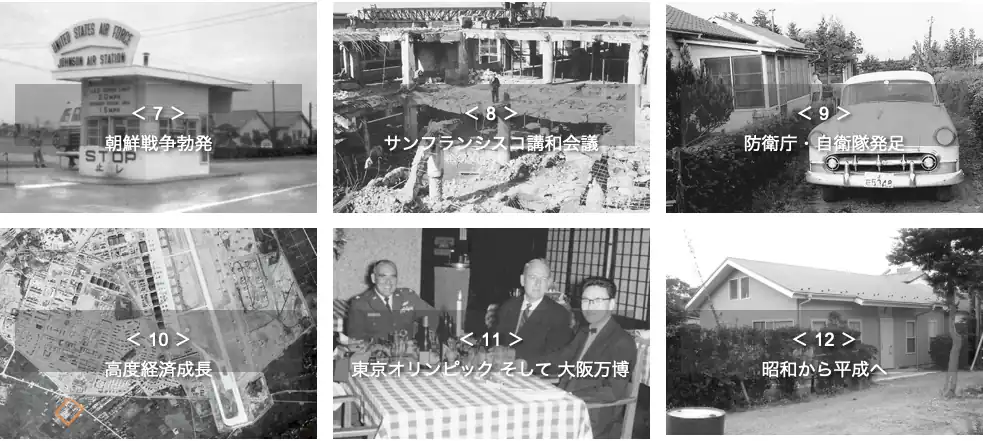

— JASDF Iruma Air Base next to the town used to be called Johnson Air Base after it was condemned by the U.S. forces after the war. This is the origin of Johnson Town, right? When the Korean War broke out in 1950, the number of U.S. military forces in Japan was increased and housing became scarce. Then, Beigun houses were built within the Isono housing site (Johnson Town), where the pre-war officers’ housing existed, and were let to American soldiers.

Mr. Tatsuo Isono had considered the revitalization of Isono housing since around 1996, after he assumed the presidency of Isono Shokai. From 2004, architect Mr. Osamu Watanabe joined, and they started renovation and construction to improve the residential site. It is striking that you thought about preserving the housing since 50 years ago.

Tatsuo: That is because we had an asset called Beigun houses. In this area, there used to be many Beigun houses. If you took a walk, you would bump into them. When I was a young child, I remember that if I visited the houses with my father, a soldier would invite us to his house and treat us with a cake and a cup of tea.

I used to work for a manufacturing company for a long time, and had an experience staying in the U.S. east coast area. My impression of private housing there very much overlapped with Beigun houses. They are memorable houses.

However, they started to be demolished as Japan grew economically. The land owners were civilians, and they started to transform them into cheap two-story apartments. We were the only ones who did not do anything about them. That is why they happened to remain.

— Currently, I think many people do not know the existence of Johnson Air Base, which is the origin of the name. The website of Johnson Town also tells of the history of the area.

Tatsuo: The site was condemned by the U.S. military after the war. This is part of the Iruma history. However, many people are not aware of this. Once it was even called a negative asset. Just like the U.S. military base in Okinawa, people seem to have a negative image of a military base.

I am not sure whether that is the reason. But people, including the public administration, do not mention that time, and treat it as if it were deleted by an eraser. We cannot even find materials in libraries and museums. I thought, if we were the only ones to save this housing, we had better continue to preserve it.

Did not aim to be American

— I heard that although Japanese started to live here after the withdrawal of American civilian military, it started to become old and run-down.

Tatsuo: It became run-down and dwellers also became old. Although the rent price was cheap and less than 20 thousand yen, arrears amounted to more than 20 million yen in total. The environment was awful, and I thought it had to be cleaned up one day.

Of course, it is a business. One way to go is to demolish everything and clear the land and develop it. However, that would mean we would have to have the residents evacuate, as it was rental housing. Such an arrangement is troublesome. Thus, we thought we would clean the units up one by one, using what we had at that time.

— Beigun houses were preserved and renovated, and Showa-era houses were reconstructed as “Heisei houses,” which inherits the DNA of Beigun houses. Streets and squares were overhauled, and the area was reborn as a town consisting of about 80 buildings including housing and shops.

Osamu Watanabe (Osamu Watanabe Architects): When Mr. Isono was consulting experts about what to do with Isono housing, I was contacted and joined the project. I felt that President Isono wanted to preserve it, even if he did not explicitly mention so.

People tend to think that it succeeded commercially by making it American-style. However, that was not our intention at all. We wanted to make an inclusive community. Isono Shokai has always been focusing on social contribution activities, such as lending the whole building to a group of disabled people. It has built a good relationship with the area. We thought that we wanted to pass on the contribution to the town and its history. The garden city in the U.S. where I lived was created to solve social problems such as child poverty, DV, and neglect.

— But this is a rather vast piece of land. Didn’t many people approach you and try to convince you to demolish it and work on a large-scale development?

Watanabe: Everybody said it would be far more profitable to clear the land and build condominiums. However, we had lots of experience in renovating crumbling buildings. So, although we knew that it would be troublesome to renovate, we also knew that there was a way to do it inexpensively.

But for contractors it is beneficial for their business to rebuild. Architects also want to earn design fees, and they similarly recommend it. As a result, it was not so simple. It is not easy to maintain an old building.

Akio Isono (Executive managing director): I did not have any memories like my father. Thus, at first I thought it would be better to rebuild after clearing the land. Even in the 2000s, there were places in this area where the sewage system was not fully equipped. When there was torrential rain, sometimes pumped sewage would flow back and float to the surface. I thought it had to be fundamentally renewed.

— Was it decided that the sewage infrastructure would also be overhauled at the time of rebuilding?

Akio: Before demolition, we negotiated with the city, and concluded an agreement that the city would build the main pipe, and the connecting sewage pipe from the housing would be arranged by us. As we rebuilt them, little by little, we increased the sewage arrangement rate.

Watanabe: The government only takes care of the area within public roads. Most of the site here consists of private roads, with some exceptions. Moreover, it was modified and newly built in a way that it would not constitute a development. Therefore, its infrastructure was left behind from the public arrangement. Normally it would be demolished and arranged at once, but the sewers were in fact renovated one by one, along with renovation and reconstruction.

There are Beigun house admirers

Tatsuo: Beigun houses are buildings that the GHQ ordered to make, modeled after American northeastern residences. There is little unevenness, and after stepping into the house with one’s shoes on, there is no foyer, and immediately there is a living room. The windows are basically small and ill-ventilated. They are not adapted to Japanese weather and customs, and are difficult to live in as they are. Some people lived there as a last resort during housing shortage, or America-oriented youngsters lived there.

Akio: Even in such situation, Beigun house had admirers, and some people traveled from far away telling us that they wanted to rent it.

Tatsuo: Three to 4 people came to visit us. One of them was a painter. I was wondering why the person was attracted to such a shabby place. The painter wanted to use it as an atelier, which could be stained, and very much liked the free and spacious atmosphere.

I rediscovered that Beigun houses have some value. This experience encouraged my lingering thoughts.

Acquisition cost of land is considered to be zero

— Roomy space is one of the charms of Johnson Town. This ampleness is surprising for a rental property.

Tatsuo: At the site where normally 2 or 3 houses would built in Japan, we built only one, which can be considered a wasteful use of land. In addition, between the houses, there are no fences, and the boundaries are unclear. As it is all our land, it doesn’t really matter (laughs).

The land was acquired when it was cheap. When regenerating it, we considered the acquisition cost as zero and came up with a profitable line of rental housing units.

— That is why it could work out as rental housing units. Taking the land price into account, we cannot be profitable unless we sell it in lots. That is something unique.

Tatsuo: As far as our research showed, we could not find any other rental housing towns with shops. That also makes it attractive.

Watanabe: When the American Institute of Architects (AIA) came for inspection, they said, “Such a community does not exist in the U.S.; it’s great.” They said that in the U.S., there were zoning regulations, and residential land could not be mixed with commercial areas, unlike here.

Bricolage was possible due to a lack of budget

Watanabe: In any case, it was possible, because we were on a tight budget. I think cutting costs and pursuing cost efficiency generated this atmosphere. It looks really plain.

We made use of what was already there. We did not discard the scrap materials but used them to cover the terrace, and we reused the roof tiles. We really did not spend much money at all. On the other hand, if we had a sufficient budget and made luxurious rental housing units, it would not become a town like this. It might have looked unpleasant.

— In the end, it turned out to be a bricolage-like method. Diversity and tolerance were generated, and some margins were left in the space. This would not be possible through deliberate design.

Tatsuo: Mr. Watanabe made great efforts to cut costs, and with his passion to preserve Johnson Town, his efforts went beyond business. It was fun to see it coming together. I also came here frequently to do hands-on work.

Akio: The president’s policy is “we use what we can use.” In our time it may be commonsensical, but he has been practicing it since 20 years ago. We went as far as using troublesome scrap materials, which would not be possible if we used a demolition company. The president himself procured materials.

Tatsuo: At that time, everybody was still discarding things unconsciously. However, I am from a time when old materials were more expensive than personnel costs. Thus, I could not throw them away because I felt it would be a pity to do so. Therefore, whatever they are, I save them and I pile up rubbish that we may not even use (laughs).

Tatsuo: To lower the cost, we established an operation company of Johnson Town and hired a construction manager. We do ourselves everything that is normally done by outsourcing.

Watanabe: We picked out Mr. Koji Shiraishi, who worked for a company that built Beigun houses, and he joined us. He was a first-class registered architect, who had a very good taste and could draw.

Tatsuo: Mr. Shiraishi was very happy to work with us. We also had similar aesthetic value. If we hadn’t had this encounter, perhaps we would not have got this far.

Watanabe: Isono Shokai orders and collects materials on its own and has carpenters make things, so it was also playing the role of a building contractor. It realized cost-cutting by doing that.

Design method to preserve the value of old things is necessary

Watanabe: In fact, what we struggled the most with was how we should fix old things. For example, a photography company would tell us not to paint the rusty parts. Many people value old materials. Such materials can only be made by the passage of time. There is no way to make them artificially. Materials made by time are valuable.

However, postwar Japan has continued the culture to consume, discard, and buy new things. Therefore, the skill to renovate and continue to use old things had not been established, and we struggled there.

How to preserve the value created by time. The design method of how to reinforce and renovate old things will be definitely necessary toward the future.

Cost-effectiveness is prioritized to determine the design

Watanabe: Beigun houses at the base were created by prioritizing cost efficiency under the conditions of achieving maximum space with minimum materials, creating a rich streetscape, and realizing the shortest construction period, as instructed by the GHQ to the Japanese design team. We could say that it is the very DNA of Beigun houses.

This house is a private-induced type (built by a private company after public administration’s prior investment) and different from that. However, it was also created with similar values in mind. The roof is made with a slope such that roof workers will not slide down and fall, and making temporary structures unnecessary. The design is not based on aesthetic beauty. Cost-effectiveness comes first and foremost. We also inherited this DNA and devised Heisei houses, assuming it to be the future standard design using modern rational structures, materials, and parts.

— How did you proceed with the renovation of the Beigun houses?

Watanabe: As they were really dilapidated, it took some time to figure out how make the them habitable. However, it is often the case that we get good ideas when we prioritize cost-effectiveness.

In the end, we jacked it up, did the groundwork again, replaced the entire foundation and rotten pillars, and reinforced the structure. We inserted insulating materials of urethane foam under the floor and in the walls, making thermal insulation performance quite high, higher than modern newly constructed buildings.

As for the Heisei houses, in order to cut costs and increase efficiency, we skipped the wooden floor, and embedded the floor heating pipes directly in the slab*. Concrete floors were easier to transform into shops, allowing people to have dogs, and increased the level of freedom of the space.

Moreover, we heard the wishes of the residents and reflected them in the design or responded to renovation demands regarding interior design. In some cases we removed the pillar and changed the partitions. We handle things flexibly. Each individual creates a different world. That is why the streets are diverse yet unified.

*Floor slab. Structural slab that supports floors of the concrete structure constructions.

Key to the design: by managing it as a private site, a town could be created where everybody including children, elderly people, and people with disabilities can live safely and peacefully. Besides renovating old houses and building new ones, it encourages communication by creating a place to hang out on streets and in squares. It became a town where it is comfortable to raise children, people can realize their dreams, and old people and people with disabilities can also live and work.

Management toward an ideal town

Tatsuo: In current Japan, there are no regulations on landscaping, and the colors and shapes of residential roofs are varied. Before the war, Japanese houses with black tiled roofs made the streetscape. It could be the case that they just did not have any other construction materials. We are free to do anything. That is now a characteristic of Japan. Thus, streetscapes are varied.

Even if an architect took the trouble to design a residential area, it could become in disarray, depending on the residents. The landscape can be maintained because there is a specific series of houses. We also need greenery, flowers, and gardens. Otherwise, it will not be an attractive town.

The time after people started living here is important. Thus, we established an office on site to offer resident services and management. From time to time we convey our policies.

Watanabe: We are always on site and deal with various consultations and complaints.

— Your task is not over just by building it. You respond to issues during the residency. That is why you can maintain the streetscape.

Johnson Town, the one and only rental housing town. Not only the designing of buildings but also by focusing on community design, it gave a foundation for the creation of a community where various people come together, including child-rearing families, creators, elderly people, and people with disabilities. In Part 2, we hear about creating an inclusive community.

Johnson Town

Isono Shokai Co., Ltd. / Osamu Watanabe Architects

A run-down residential site for the U.S. military was revitalized as a rental housing site. Based on the strong will of the land owner and the architect, the exterior maintained a unified impression of an architectural group consisting of Beigun houses and Heisei houses, while the interior was boldly renovated according to the requests of residents, pursuing an ideal living environment. They are aiming to create an inclusive town by considering accessibility, for example, by cooperating with social welfare corporations. People sharing such direction came together, and shops and activities have expanded, creating a unique streetscape and lifestyle.

- Award details

- 2021 GOOD DESIGN GOLD AWARD “Johnson Town” https://www.g-mark.org/en/gallery/winners/9e5e871f-803d-11ed-af7e-0242ac130002?years=2021

- Producer

- Tatsuo Isono, Akio Isono, Isono Shokai Co., Ltd.

- Director

- Tatsuo Isono, Akio Isono, Isono Shokai Co., Ltd. + Osamu Watanabe, Osamu Watanabe Architects

- Designer

- Osamu Watanabe, Mami Kawai, Miyuki Saito, Yumi Ohzawa, Arisa Mae, Norie Sakamoto, Osamu Watanabe Architects

Tomoko Ishiguro

Editor/writer

After working in the editorial department of “AXIS,” she became a freelancer. She writes, edits, and plans, with a focus on design and life culture. Her major editorial works include LIXIL BOOKLET series (book, LIXIL Publishing) and “Oishisa no Kagaku” (magazine, NTS Publishing).

Chieko Shiraishi

Photographer

She started photography after taking a black and white enlarger lesson organized by a town. After working as an assistant photographer, she is mainly active in taking photos for magazines, etc., while creating works in a darkroom.